Complicações

Secondary bacterial and fungal skin or soft-tissue infections may occur.[182][197] The vesicular skin rash results in a breach of the integrity of the cutaneous barrier to bacterial skin infection, especially when scratched or otherwise traumatized. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections, soft-tissue abscesses, cellulitis, paronychia, acral lesions (whitlow), bacterial superinfection, lymphangitis, hypertrophic verrucous lesions, and pyomyositis have all been reported.[1][200][289][337][338][339][340][341] Antibiotic treatment is recommended. Surgery may be required, with some cases requiring extensive surgical debridement or amputation of an affected extremity.[197][342] Permanent pitted scarring and discoloration secondary to infection is a common long-term sequelae.[5][182]

Patients with a heavy rash burden may develop exfoliation, similar to partial thickness burns in severe cases. Lesions can coalesce until large sections of skin slough off. Minimize insensible fluid loss and promote skin healing. Ensure adequate hydration and nutrition. Debridement may be needed. Skin grafting may be required rarely.[1]

Can occur in up to 86% of cases with lymphadenopathy. When combined with multiple oropharyngeal lesions, patients may be at risk of retropharyngeal abscess or respiratory compromise. Corticosteroid treatment may be required.[1]

Secondary bacterial infections causing sepsis have been reported rarely.[335] Identification of sepsis should be done rapidly using established criteria. Management follows the same principles as for bacterial sepsis and should include: broad-spectrum empirical antibiotic therapy, ideally given within 1 hour of recognition; rapid intravenous fluid resuscitation with assessment of response; vasoactive therapy; appropriate airway management and oxygen administration.[336]

May occur in severe disease because intravascular fluid tends to be lost through fever, rash, and capillary leak. The accompanying systemic inflammatory response syndrome may cause hypotension as well. This combination of factors reduces renal blood flow and promotes acute kidney injury. Early recognition by monitoring urine output and blood biochemistry will indicate whether intravenous fluids are necessary.

Patients are at risk of bacterial pneumonia.[5] Pulmonary involvement with nodular lesions has been reported.[197] The risk of ventilation and pneumonitis were lower during the 2022 global clade II mpox outbreak compared with previous outbreaks.[343] Broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment should be given. Severe pneumonia will cause hypoxia requiring oxygen therapy and possibly mechanical ventilation in an intensive care unit.

Hypotension may be exacerbated by superadded bacterial sepsis and possible viral myocarditis. Hypotension unresponsive to adequate fluid replacement will require treatment with inotropes. If superadded bacterial sepsis is suspected, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given intravenously.

Cases of myocarditis, pericarditis, and myopericarditis have been reported rarely. The most common presentation is chest pain. Cases are usually self-limiting and require supportive care only.[344][345] Consider cardiology consultation and standard of care treatment. Mpox antiviral therapy may play a role by limiting viral spread. Other causes should be investigated (e.g., recent receipt of a vaccine that is associated with myopericarditis such as a COVID-19 vaccine).[229] Other cardiovascular complications (e.g., heart failure, arrhythmias) are also possible.[346]

Ocular manifestations are uncommon, but may result in corneal scarring and permanent vision loss.[182] They may occur as a result of autoinoculation. Patients may present with conjunctivitis, blepharitis, keratitis, keratoconjunctivitis, uveitis, subconjunctival nodules, or periorbital cellulitis. Ocular involvement appears to be rare in the 2022 global clade II mpox outbreak, with approximately 1% of patients affected (compared with 9% to 23% in previous outbreaks).[347][348] Conjunctivitis was the most common ophthalmic complication of mpox (pooled prevalence of 9%).[349] Conjunctivitis may be an early predictor for severe disease progression.[256] Ocular involvement has been reported in neonates.[350] Isolated ocular manifestations have been reported without the presence of skin lesions.[351]

Ophthalmic consultation is recommended in patients with ocular involvement. Slit-lamp exam and dilated funduscopic exam may be helpful for determining whether anterior or posterior segment structures are involved.[352]

Vitamin A supplementation is recommended. Eye lubrication and saline-soaked eye pads may be helpful. Ophthalmic antibiotics/antivirals may be required for coinfection.[1] Advise patients not to wear contact lenses.[273] Topical trifluridine (also known as trifluorothymidine) may be considered in cases of conjunctivitis, and is recommended for the management of keratitis, in consultation with an ophthalmologist. It may also be used prophylactically in patients with lesions on their eyelids, near the eye, or in children ages <8 years and others unable to follow instructions about hand hygiene and avoidance of hand-eye contact to prevent autoinoculation; however, the risk of corneal epithelial toxicity with prolonged use must be taken into account, and it should only be used under specialist guidance. Topical corticosteroids should be avoided as they may cause corneal damage or viral persistence.[352]

Oral tecovirimat should be considered for all patients with severe disease, which includes ocular manifestations. Case reports on its use for ocular complications have been published.[353][354] Other antivirals and therapeutics may be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Vaccinia immune globulin may be considered on a case-by-case basis in consultation with an infectious disease specialist. However, caution is recommended in people with active keratitis, as increased corneal scarring was observed in one animal model study. A second animal model study showed no corneal scarring. There are limited data in humans.[352]

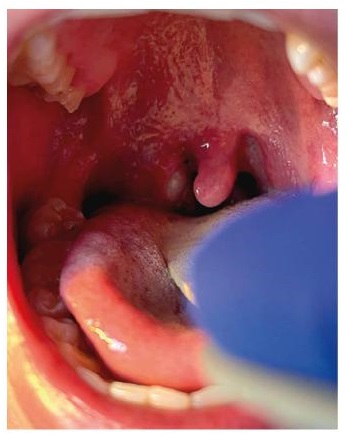

Tonsillar complications were not previously known to be typical. However, they have been reported rarely in the 2022 global clade II mpox outbreak (e.g., tonsillitis, peritonsillar cellulitis, tonsillar/peritonsillar abscess, necrotizing tonsillitis), likely as a consequence of practising oral-receptive sex.[111][200][205][355][356][357] Airway management, antibiotic therapy, and surgery may be required depending on the presentation.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Right tonsillar enlargement with an overlying pustular lesion and yellow-green exudate with slight deviation of the uvulaBMJ. 2022 Jul 28;378:e072410; CC-BY-NC 4.0 licence [Citation ends].

Epiglottitis was not previously known to be a typical complication. However, it has been reported rarely in the 2022 global clade II mpox outbreak.[111] Urgent management, particularly of the airway, may be required.

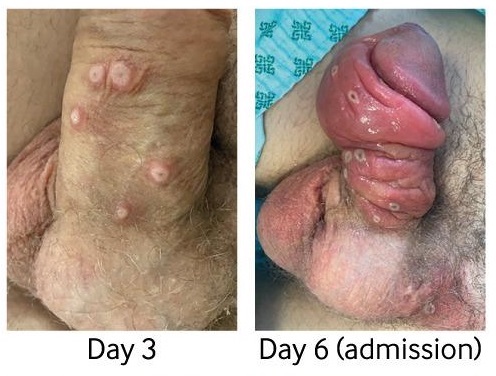

Paraphimosis/phimosis was not previously known to be a typical complication. However, it has been reported rarely in the 2022 global clade II mpox outbreak as a consequence of lesions causing severe penile/scrotal edema.[200][205][226][358][359][360] Paraphimosis is a medical emergency and surgery may be required if there is evidence of ischemia or necrosis.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Progression of penile lesions and penile edemaBMJ. 2022 Jul 28;378:e072410; CC-BY-NC 4.0 licence [Citation ends].

Perianal/groin abscesses and rectal perforation were not previously known to be typical complications. However, they have been reported rarely in the 2022 global clade II mpox outbreak.[200][205][361][362] Bowel lesions may be exudative and cause significant tissue edema leading to obstruction. Lesions may lead to bowel strictures and scarring.[197] Proctitis-associated bowel obstruction has been reported.[363] Antibiotic therapy and surgery may be required. Severe rectal bleeding (associated with proctocolitis) requiring transfusion has been reported.[364]

Urinary retention (e.g., due to severe penile edema or urethritis) was not previously known to be a typical complication. However, it has been reported rarely in the 2022 global clade II mpox outbreak.[200][226][365] Lesions may lead to urethral strictures and scarring. Catheterization may be required.[197] Cold compresses may help with penile edema.[273]

Patients with severe disease are at risk of encephalitis/meningoencephalitis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, transverse myelitis, and seizures, although neurologic complications are considered to be rare.[5][197][368][369][370] Few neurologic complications have been reported with the 2022 global clade II mpox outbreak.[369][371] However, cases of encephalomyelitis and Guillain-Barre syndrome have been reported.[372][373][374][375] A case of Parsonage-Turner syndrome (brachial neuritis) has been reported following infection and vaccination.[376] It is unknown whether this is a result of direct viral invasion of the central nervous system, or whether it is a parainfectious autoimmune process triggered by systemic infection.

Treatment is primarily supportive. Consider neurology consultation. There may be a role for mpox antiviral agents and their use should be considered, but there is no supportive evidence. Antibiotics/antivirals may be indicated for coinfections. Immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive treatment may be required. Anticonvulsants should be administered if required.[1][229]

A rare case of severe disseminated infection complicated by peritonitis has been reported in the 2022 global clade II mpox outbreak. The patient was successfully treated with tecovirimat without requiring surgery.[381]

Subacute thyroiditis can occur after viral infections. A case of subacute thyroiditis after mpox infection has been reported in the 2022 global clade II mpox outbreak. The patient had well-controlled HIV infection and was on antiretroviral therapy. They were treated with a corticosteroid and levothyroxine.[382]

A severe, disseminated, necrotizing form of disease has been reported in patients with advanced immunosuppression (e.g., CD4 cell counts <100 cells/microliter and/or high HIV viral loads, hepatitis B coinfection) in case reports and case series, and appears to behave like an AIDS-defining condition. Patients presented with widespread, large, necrotizing, and coalescing skin and mucosal lesions. Severe secondary bacterial infections were common. Some patients developed lung nodules, necrotic lung masses, nodular liver lesions, respiratory failure, or sepsis. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) was suspected in 25% of patients starting (or restarting) antiretroviral therapy after diagnosis. Death was reported in 15% of patients, mostly in those with CD4 cell counts <200 cells/microliter.[152][341][377][378][379][380]

Immune function should be optimized in moderate-to-severely immunocompromised patients with uncontrolled viral spread. Promptly start treatment with tecovirimat, and consider the addition of either cidofovir or brincidofovir and vaccinia immune globulin. Extended treatment courses may be required. Wound care is critical. Fluid management may be required. Consider specialist consultation, as indicated. Closely monitor for complications.[229]

Inoculation with traditional vaccinia (first- or second-generation vaccines) may cause eczema vaccinatum (a generalized vesicular rash in the presence of eczema), generalized vaccinia (a self-limiting illness consequent upon vaccinia viremia occurring in the absence of preexisting skin disease), or progressive vaccinia. Progressive vaccinia starts as a localized but relentlessly progressive spread of vaccinia at the inoculation site and is potentially fatal. It occurs in the markedly immunosuppressed (e.g., congenital immunodeficiencies, cytotoxic chemotherapy, advanced HIV disease). Progressive vaccinia is rare, but fatal if untreated. Tecovirimat (or other antivirals) or vaccinia immune globulin are options for the treatment of complications due to vaccinia vaccination.

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Eczema vaccinatum skin lesions on the torso of a smallpox vaccine recipientCDC/Moses Grossman, MD/California Emergency Preparedness Office (Calif/EPO) [Citation ends].

O uso deste conteúdo está sujeito ao nosso aviso legal