Approach

Patients may present with a subacute cough, most commonly postinfection; however, in most patients, postinfectious cough is self-limited.[6] Observation and, if required, symptomatic therapy may be all that is needed in these patients. Once the cough persists for longer than 8 weeks, further evaluation is indicated.[37][38] Several validated tools of cough assessment are available, although these are used mostly for research purposes.[39]

Pursuing the cause and resolution of chronic cough requires ongoing commitment to the patient. The approach to an individual patient with chronic cough may vary from full initial diagnostic evaluation for common associated diseases, to empiric but targeted therapy for common conditions known to cause chronic cough, with limited or no diagnostic efforts.[10] Choice of the specific approach may be individualized, and depends on type and duration of symptoms, the patient's preference, and availability of resources. Limiting diagnostic testing, treating assumed etiologies, and applying sequential empiric trials of therapy is most cost-effective, but leads to the longest time to resolution of cough and may be associated with increased patient anxiety.[10][40][41] In practice, diagnostic and therapeutic processes are often applied simultaneously. It is best to involve the patient in choosing the best approach and to explain the expected duration and course of diagnostic and therapeutic trials.

History and examination

A detailed history is essential, and should include:

Time and clinical setting of onset

Exacerbating factors

Associated symptoms

Prior history suggestive of atopic disease

A complete medical, smoking, drug, and exposure history

Occupational and family history

What measures have already been tried, and to what effect.

The history substantially influences the clinician's impression as to which (if any) of the four most common etiologies (upper airway cough syndrome [UACS], asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease [GERD], or nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis [NAEB]) are most likely.

A careful examination is, unfortunately, unlikely to inform the clinician regarding the commonest causes of chronic cough, but is essential for early detection of less common causes, such as bronchiectasis, interstitial lung disease, neoplastic disorders, or chronic infectious pulmonary diseases.

Although no specific history or physical exam findings are reliably associated with specific etiology of chronic cough, they may direct further testing or therapeutic trials.

The symptoms and findings associated with the common causes (asthma, UACS, GERD, or NAEB) may direct further diagnostic evaluation toward confirming that cause.

Asthma

May present with wheezing, chest tightness, or dyspnea apart from paroxysms of cough, or exacerbation of cough by seasonal exposures, specific irritants, or nonspecific respiratory irritants such as cold air, aromatic vapors, or dusty environments. In patients who do not ever wheeze, another cause should be considered.[10] There may be variability of symptoms, nocturnal exacerbation of cough, or a strong family history of asthma or atopic disease.[42] Cough-variant asthma, in which persistent cough is the principal or sole symptom, tends to be worse at night or with exercise.[11][43]

UACS

A clinical syndrome and diagnosis is based on the clinical picture (which includes frequent throat clearing, postnasal drip, nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, and sneezing) and response to therapy.[44] Potential causes of UACS include allergic rhinitis, perennial nonallergic rhinitis, postinfectious rhinitis, bacterial sinusitis, allergic fungal sinusitis, rhinitis due to anatomic abnormalities, nasal polyposis, rhinitis due to physical or chemical irritants, occupational rhinitis, rhinitis medicamentosa, and rhinitis of pregnancy.[44]

GERD

May present with heartburn, dysphagia, acid regurgitation, and an associated cough with slouched posture. Suggestive symptoms may include cough on phonation, cough on rising from bed, or association with certain foods or with eating in general.[10] Reflux disease is clinically silent in up to 75% of cases.[45] Extra-esophageal symptoms of GERD (chronic cough, asthma, laryngitis, and dental erosions) can occur without typical GERD symptoms.[46]

NAEB

Presents with a chronic, generally scantily productive or nonproductive cough without prominent features of asthma or reliable cough triggers, although patients may complain of wheezing at times.

ACE inhibitor cessation

The cough from an ACE inhibitor may begin within days or months of onset of ACE inhibitor therapy. If use of ACE inhibitors is suspected as the cause, use should be stopped if at all possible. Diagnosis is then confirmed by the resolution of cough, usually within 1 to 4 weeks (although it may be up to 3 months).[47] Angiotensin receptor blocking agents do not appear significantly related to chronic cough symptoms.

Chest x-ray

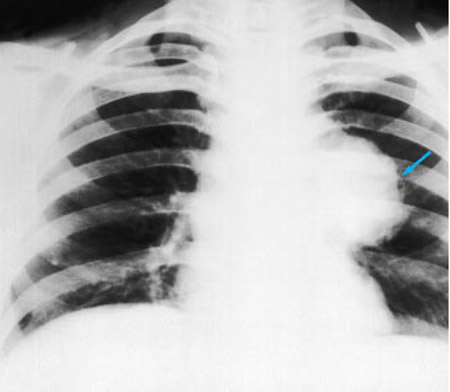

A chest x-ray should be obtained early in the evaluation of chronic cough.[38] Although it is not diagnostic of the most common causes, findings may quickly divert the evaluation to causes of greater gravity, such as structural lung diseases. These include lung cancer, tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, pneumonia, aspiration, and sarcoidosis.[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing bilateral hilar adenopathy in a patient with sarcoidosisFrom the personal collection of Dr M.P. Muthiah, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, University of Tennessee [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing multiple miliary lung metastases (arrows). The primary tumor was a thyroid carcinomaE. Dick, Student BMJ. 2001;9:10-12 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing multiple miliary lung metastases (arrows). The primary tumor was a thyroid carcinomaE. Dick, Student BMJ. 2001;9:10-12 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing left hilar carcinoma (arrow)From: E. Dick, Student BMJ. 2000;8:358-360 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing left hilar carcinoma (arrow)From: E. Dick, Student BMJ. 2000;8:358-360 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing a cavitating right hilar carcinoma (arrow)E. Dick, Student BMJ. 2001;9:10-12 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing a cavitating right hilar carcinoma (arrow)E. Dick, Student BMJ. 2001;9:10-12 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray in a patient with bronchogenic carcinoma showing a left-sided pleural effusionFrom: R. Thakkar, Student BMJ. 2001;9:458 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray in a patient with bronchogenic carcinoma showing a left-sided pleural effusionFrom: R. Thakkar, Student BMJ. 2001;9:458 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing pulmonary tuberculosis with cavitationFrom the personal collection of Dr M. Narita, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Washington [Citation ends].

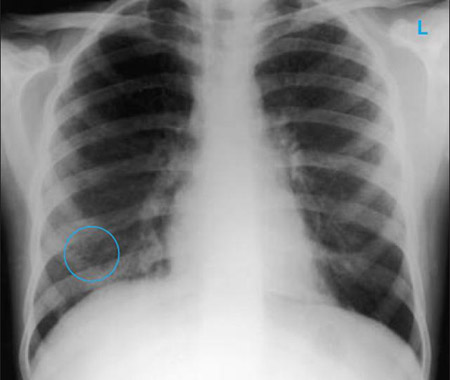

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing pulmonary tuberculosis with cavitationFrom the personal collection of Dr M. Narita, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, University of Washington [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing multiple discrete nodules throughout both lungs (one of which is circled) in a patient with miliary tuberculosisE. Dick, Student BMJ. 2001;9:10-12 [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing multiple discrete nodules throughout both lungs (one of which is circled) in a patient with miliary tuberculosisE. Dick, Student BMJ. 2001;9:10-12 [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray with lack of normal tapering producing a tram line in a patient with bronchiectasisFrom the personal collection of Dr S.M. Bhorade, University of Chicago Medical Center; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray with lack of normal tapering producing a tram line in a patient with bronchiectasisFrom the personal collection of Dr S.M. Bhorade, University of Chicago Medical Center; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray with dilated and thickened airways in a patient with bronchiectasisFrom the personal collection of Dr S.M. Bhorade, University of Chicago Medical Center; used with permission [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray with dilated and thickened airways in a patient with bronchiectasisFrom the personal collection of Dr S.M. Bhorade, University of Chicago Medical Center; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing increased opacification of the right perihilar region and superior segment of the right lower and upper lobes consistent with worsening aspiration pneumoniaFrom the personal collection of Dr R. Kanner, University of Utah School of Medicine [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing increased opacification of the right perihilar region and superior segment of the right lower and upper lobes consistent with worsening aspiration pneumoniaFrom the personal collection of Dr R. Kanner, University of Utah School of Medicine [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing early ill-defined opacities of the right upper lobe above the minor fissure consistent with early changes of aspiration pneumoniaFrom the personal collection of Dr R. Kanner, University of Utah School of Medicine [Citation ends].

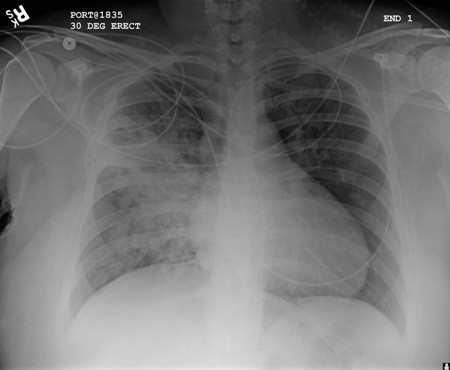

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest x-ray showing early ill-defined opacities of the right upper lobe above the minor fissure consistent with early changes of aspiration pneumoniaFrom the personal collection of Dr R. Kanner, University of Utah School of Medicine [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Portable chest x-ray with bibasilar opacities, worse on the right than the left, in a patient with hospital-acquired pneumoniaFrom the personal collection of Dr F.W. Arnold, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Louisville School of Medicine [Citation ends].

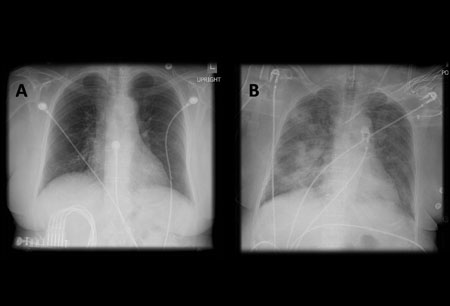

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Portable chest x-ray with bibasilar opacities, worse on the right than the left, in a patient with hospital-acquired pneumoniaFrom the personal collection of Dr F.W. Arnold, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Louisville School of Medicine [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A. Portable upright chest x-ray before aspiration; B. Chest x-ray 1 hour after aspiration, showing bilateral diffuse alveolar infiltrates, worse at the bases on the right sideFrom the personal collection of Dr S. Murgu and Dr H. Colt, University of California at Irvine Medical Center [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: A. Portable upright chest x-ray before aspiration; B. Chest x-ray 1 hour after aspiration, showing bilateral diffuse alveolar infiltrates, worse at the bases on the right sideFrom the personal collection of Dr S. Murgu and Dr H. Colt, University of California at Irvine Medical Center [Citation ends].

Choice of diagnostic testing or therapeutic trials

Following chest x-ray, the choice of either diagnostic testing or therapeutic trials depends on the clinician's assessed probability of a specific etiology and the patient's preferred approach.[38] Unless the history, physical examination, and chest x-ray indicate otherwise, efforts should be concentrated on one or more of the four most common causes (asthma, UACS, GERD, NAEB).

For example, if the history is most suggestive of asthma, then spirometry or assessment of peak expiratory flow (to test for airway obstruction) and bronchodilator variability testing would be appropriate first tests.[11][30][31] Other investigations include fractional exhaled nitric oxide and bronchoprovocation challenge testing (e.g., methacholine inhalation test). Noninvasive tests to predict response to inhaled corticosteroids also include blood and sputum eosinophil counts, and blood and sputum eosinophilic cationic protein (ECP).[43] In the presence of raised blood or sputum eosinophil counts, negative reversibility tests should prompt consideration of a diagnosis of NAEB.

If UACS is suspected, a therapeutic trial aimed at resolving rhinosinusitis and reducing excessive secretions is indicated.

A therapeutic trial of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is recommended for patients with typical GERD symptoms (heartburn and regurgitation).[48] Diagnostic testing (including esophageal pH monitoring and endoscopy) may be considered according to clinician or patient preference in those refractory to a therapeutic trial of PPIs, or where there is a strong clinical suspicion of reflux-related cough.[48][49] In patients with extra-esophageal manifestations of GERD without typical GERD symptoms, consideration should be given toward diagnostic testing for reflux before initiation of PPI therapy.[46]

Laboratory tests

Laboratory assessment of sputum production is a key factor in narrowing the differential, as it can indicate presence of an infectious cause. If the cough is productive, a sputum sample should be sent for Gram stain and culture. Depending upon the history and examination, the following blood tests might be taken: CBC, WBC count, CRP, total IgE blood test for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.

Further diagnostic evaluation

If none of the four most common causes seem likely after thorough assessment, other tests to consider include:

High-resolution CT imaging of the chest to look for bronchiectasis (which does not always promote a productive cough), foreign body aspiration, pulmonary fibrosis, or other structural lung disease (which may not show well on chest x-ray). Chronic suppurative lung disease is diagnosed in patients with clinical symptoms of bronchiectasis but no radiographic evidence of bronchiectasis.[50] CT imaging may also indicate the presence of an aortic aneurysm or Zenker diverticulum. The diagnostic yield of the CT scan of the chest in a patient with chronic cough and normal chest x-ray is expected to be low.[3][Evidence C] There is no high-quality evidence to support the use of chest CT in the initial evaluation of patients presenting with chronic cough.[38]

Bronchoscopy to search for endobronchial pathology.

CT sinuses or nasendoscopy.

24-hour esophageal pH and/or impedance monitoring to rule out silent GERD.

Serum ferritin and iron, because iron deficiency has been associated with chronic cough.[51]

Serum alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) levels should be quantified in individuals with possible AAT deficiency. However, AAT is an acute phase reactant, meaning that normal serum AAT levels can be misleading, especially in the setting of inflammatory processes.[52]

Polysomnography or polygraphy to rule out obstructive sleep apnea.

In addition, pulmonary and/or ENT consultation should be considered. In cases where the patient also has features of stridor, laryngospasm, or paradoxical vocal fold motion, early involvement of a speech pathologist is appropriate, because treatment directed at underlying causes may speed resolution of chronic cough as well.[53]

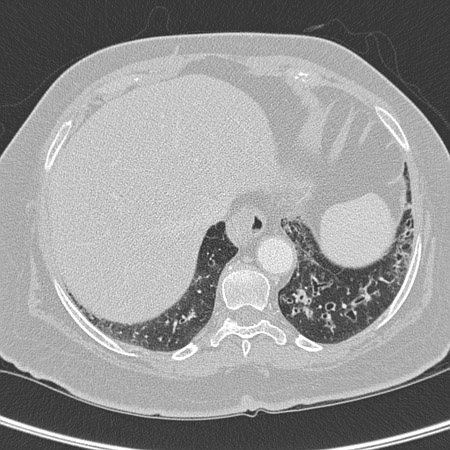

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT with presence of signet ring on left in a patient with bronchiectasisFrom the personal collection of Dr S.M. Bhorade, University of Chicago Medical Center [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT with dilated and thickened airways and peripheral tree-in-bud pattern in a patient with bronchiectasisFrom the personal collection of Dr S.M. Bhorade, University of Chicago Medical Center; used with permission [Citation ends].

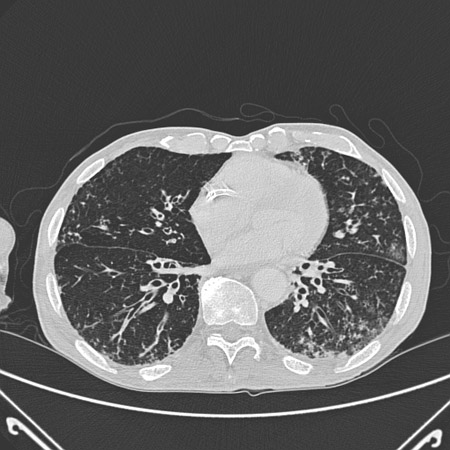

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT with dilated and thickened airways and peripheral tree-in-bud pattern in a patient with bronchiectasisFrom the personal collection of Dr S.M. Bhorade, University of Chicago Medical Center; used with permission [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT of the chest with intravenous contrast material showing complete left lower lobe collapse with a radiopaque object within the left lower main bronchus surrounded by a halo of airBMJ Case Reports 2008 (doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0013). Copyright 2008 BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: CT of the chest with intravenous contrast material showing complete left lower lobe collapse with a radiopaque object within the left lower main bronchus surrounded by a halo of airBMJ Case Reports 2008 (doi:10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0013). Copyright 2008 BMJ Publishing Group Ltd [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT showing idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisFrom the personal collection of Dr J.C. Munson, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine [Citation ends].

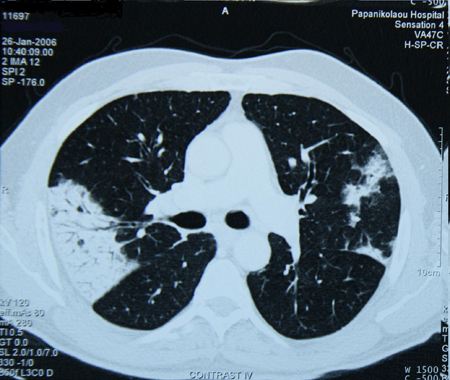

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT showing idiopathic pulmonary fibrosisFrom the personal collection of Dr J.C. Munson, Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT of a patient with amiodarone pulmonary toxicity, showing asymmetric opacities with a peripheral distributionFrom the personal collection of Dr A. Pataka and Professor P. Argyropoulou, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Chest CT of a patient with amiodarone pulmonary toxicity, showing asymmetric opacities with a peripheral distributionFrom the personal collection of Dr A. Pataka and Professor P. Argyropoulou, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bronchoscopy image showing a loquat seed completely occluding the bronchus intermediusFrom the personal collection of Dr S. Murgu and Dr H. Colt, University of California at Irvine Medical Center [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Bronchoscopy image showing a loquat seed completely occluding the bronchus intermediusFrom the personal collection of Dr S. Murgu and Dr H. Colt, University of California at Irvine Medical Center [Citation ends].

Therapeutic trials

Therapeutic trials are selected based on clinical impression, at times supported by diagnostic testing. The patient's response to the trial must be assessed and the cough resolved before a given etiology may be assigned with certainty. A partial response may indicate that more than one etiology is in play. In this event, further testing and/or additional therapeutic trials may be indicated, while the partially successful therapy should be continued. Lack of a response requires reassessment both of suspected etiology and of treatment adherence and effectiveness. High placebo effect has been reported in empiric trials in chronic cough.[54]

Empiric therapeutic trials may be undertaken sequentially (starting with the most likely etiology first), with subsequent selections made according to patient response. Alternatively, trials may be undertaken simultaneously when multiple etiologies are suspected from the outset, with subsequent sequential withdrawal of therapies once the cough is controlled. The following are considered:

UACS: a trial of an antihistamine plus a decongestant should be undertaken. Failure of response to appropriate therapeutic trials should prompt a sinus computed tomography (CT) scan and an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) referral, particularly if other etiologies have been considered and deemed very unlikely.

Asthma or NAEB: noninvasive measurement of airway inflammation (such as fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) sputum and blood eosinophilia, and sputum and blood eosinophilic cationic protein) is suggested as a useful tool to predict response of cough to inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), based on moderate supporting evidence.[43] If eosinophilic airway inflammation is found, it is likely to respond to corticosteroids.[43] Since the availability of these noninvasive tests is limited, an empiric trial of ICS is commonly used in clinical practice. Failure of response to 2-4 week trial of an ICS should prompt an increase in the dose of the ICS with the addition of a therapeutic trial of a leukotriene receptor antagonist.[43] Beta agonists may also be considered with ICS.[43] Treatment adherence, anti-inflammatory effectiveness (measured by FeNO and peak-flow variability, as appropriate), and conditions that contribute to ongoing poor asthma control such as GERD, sinus disease, or ongoing allergen exposure, should be reevaluated.[43]

Peak flow measurement: animated demonstrationHow to use a peak flow meter to obtain a peak expiratory flow measurement.

GERD: failure of response to an appropriate therapeutic trial (e.g., 8-12 weeks with a proton-pump inhibitor) should prompt confirmatory testing (if not already done), and careful assessment of effectiveness of acid suppression and/or other factors contributing to ongoing nonacid reflux.[46][48][49]

Cough hypersensitivity syndrome: a therapeutic trial of a neuromodulator drug, such as gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline, or baclofen could be considered if previous investigations do not produce a conclusive diagnosis and cough hypersensitivity syndrome is suspected.[26]

How to use a peak flow meter to obtain a peak expiratory flow measurement.

How to take a venous blood sample from the antecubital fossa using a vacuum needle.

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer