Dysmenorrhea is one of the most common gynecological symptoms affecting the quality of life of menstruating women.[1]Fernández-Martínez E, Onieva-Zafra MD, Parra-Fernández ML. The impact of dysmenorrhea on quality of life among Spanish female university students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Feb 27;16(5):713.

https://www.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050713

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30818861?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Iacovides S, Avidon I, Bentley A, et al. Reduced quality of life when experiencing menstrual pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014 Feb;93(2):213-7.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12287

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24266425?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Al-Jefout M, Seham AF, Jameel H, et al. Dysmenorrhea: prevalence and impact on quality of life among young adult Jordanian females. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015 Jun;28(3):173-85.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26046607?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Iacovides S, Avidon I, Baker FC. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: a critical review. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:762-78.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26346058?tool=bestpractice.com

It is experienced as lower abdominal pain or uterine cramps that occur during the few days prior to and/or during menstruation, and usually subsides at the end of menstruation.

Dysmenorrhea is subcategorized into primary and secondary, although it is not always easy to distinguish between the two based on history and exam alone:

The prevalence is difficult to determine because different definitions and criteria are used, and dysmenorrhea is often underestimated and undertreated.[5]Proctor M, Farquhar C. Diagnosis and management of dysmenorrhoea. BMJ. 2006;332:1134-1138.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16690671?tool=bestpractice.com

[6]Burnett M. Guideline no. 345: primary dysmenorrhea. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2025 May;47(5):102840.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/40216328?tool=bestpractice.com

The reported prevalence of dysmenorrhea varies substantially.[7]Ju H, Jones M, Mishra G. The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36:104-13.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxt009

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24284871?tool=bestpractice.com

According to a systematic review by the World Health Organization in 2006, the prevalence of dysmenorrhea in menstruating women is between 16.8% and 81%.[8]Latthe P, Latthe M, Say L, et al. WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity. BMC Public Health. 2006 Jul 6;6:177.

https://www.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-177

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16824213?tool=bestpractice.com

A greater prevalence is generally observed in young women, with estimates ranging from 67% to 90% for those aged 17-24 years.[7]Ju H, Jones M, Mishra G. The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36:104-13.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxt009

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24284871?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Harlow SD, Ephross SA. Epidemiology of menstruation and its relevance to women's health. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17(2):265-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8654511?tool=bestpractice.com

[10]Kennedy S. Primary dysmenorrhoea. Lancet. 1997 Apr 19;349(9059):1116.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9113008?tool=bestpractice.com

An Australian study found that a higher proportion, 93%, of teenagers reported menstrual pain.[11]Parker MA, Sneddon AE, Arbon P. The menstrual disorder of teenagers (MDOT) study: determining typical menstrual patterns and menstrual disturbance in a large population-based study of Australian teenagers. BJOG. 2010 Jan;117(2):185-92.

https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02407.x

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19874294?tool=bestpractice.com

Studies in adult women are less consistent, with rates varying from 15% to 75%.[7]Ju H, Jones M, Mishra G. The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36:104-13.

https://www.doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxt009

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24284871?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Harlow SD, Ephross SA. Epidemiology of menstruation and its relevance to women's health. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17(2):265-86.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8654511?tool=bestpractice.com

Dysmenorrhea can lead to absenteeism from work or school, with up to 50% reporting at least one episode of absence, and 5% to 14% reporting frequent absence.[12]Burnett MA, Antao V, Black A, et al. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27:765-770.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16287008?tool=bestpractice.com

Factors that correlate positively with dysmenorrhea are smoking, early menarche, nulliparity, and family history.[13]Harlow SD, Park M. A longitudinal study of risk factors for the occurrence, duration and severity of menstrual cramps in a cohort of college women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:1134-42.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8917003?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]Sundell G, Milsom I, Andersch B. Factors influencing the prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhoea in young women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:588-594.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2390501?tool=bestpractice.com

Dysmenorrhea is not associated with the duration of the menstrual cycle, but it usually coexists with heavy menstrual bleeding. Many women experience delays in diagnosis and management.[15]Chen CX, Draucker CB, Carpenter JS. What women say about their dysmenorrhea: a qualitative thematic analysis. BMC Womens Health. 2018 Mar 2;18(1):47.

https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0538-8

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29499683?tool=bestpractice.com

Validated questionnaires of patient reported outcomes may be useful in the initial assessment of dysmenorrhea and in assessing response to treatment.[16]Gray TG, Moores KL, James E, et al. Development and initial validation of an electronic personal assessment questionnaire for menstrual, pelvic pain and gynaecological hormonal disorders (ePAQ-MPH). Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019 Jul;238:148-156.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31132692?tool=bestpractice.com

Primary dysmenorrhea

Primary dysmenorrhea often occurs in the 6-12 months following menarche, once ovulatory cycles have been established.[17]ACOG Committee Opinion No. 760 Summary: Dysmenorrhea and Endometriosis in the Adolescent. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec (Re-affirmed 2021);132(6):1517-8.

https://www.doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002981

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30461690?tool=bestpractice.com

It is more common in adolescents and women under 30 years, although underlying pathology may still be present. Endometriosis is common in adolescents, with a mean prevalence of 64% in girls with dysmenorrhea at laparoscopy.[18]Hirsch M, Dhillon-Smith R, Cutner AS, et al. The prevalence of endometriosis in adolescents with pelvic pain: a systematic review. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020 Dec;33(6):623-30.

https://www.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2020.07.011

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32736134?tool=bestpractice.com

Pain due to primary dysmenorrhea is usually lower abdominal and cramping in nature, and may radiate to the back and inner thigh. It usually occurs at the onset of menstruation, or precedes it by only a few hours, and typically lasts between 8 and 72 hours. The pain may be associated with other systemic symptoms such as vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, fatigue, and headache. There may also be increased sensitivity to pain.[4]Iacovides S, Avidon I, Baker FC. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: a critical review. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:762-78.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26346058?tool=bestpractice.com

The diagnosis can be made clinically. Investigations fail to reveal an underlying pelvic pathology.

Secondary dysmenorrhea

By contrast, secondary dysmenorrhea often occurs several years after the onset of menarche. It may arise as a new symptom when the woman is in her 30s or 40s in the setting of an identifiable pelvic disease. The pain is not consistently related to menstruation alone, and may occur throughout the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. It may also worsen as menses progresses rather than being confined to the first 24-48 hours of menstruation. Accompanying symptoms, such as irregular or heavy bleeding, vaginal discharge and dyspareunia can be suggestive of an underlying pelvic pathology.[19]Dawood MY. Dysmenorrhea. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1990;33:168-178.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2178834?tool=bestpractice.com

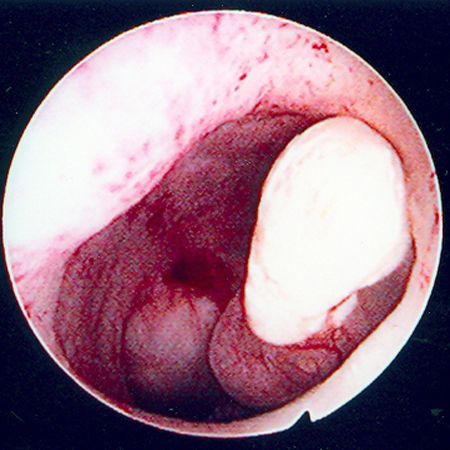

Common causes of secondary dysmenorrhea are endometriosis, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, adenomyosis, intrauterine polyps and fibroids. The presence of an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD) is a potential iatrogenic cause. Less common causes include congenital uterine abnormalities, cervical stenosis, and an ovarian pathology.

Log in or subscribe to access all of BMJ Best Practice