Summary

Differentials

Common

- Corneal ulcer

- Dry eye syndrome (tear dysfunction syndrome)

- Dry age-related macular degeneration

- Uveitis/scleritis

- Cataract

- Nondiabetic myopic lens shift

- Wet age-related macular degeneration

- Vitreous hemorrhage

- Retinal venous occlusion

- Retinal arterial occlusion

- Stroke

- Migraine headache or migraine aura without headache (acephalgic migraine)

- Pituitary tumor

- Diabetic retinopathy

- Diabetic myopic lens shift

Uncommon

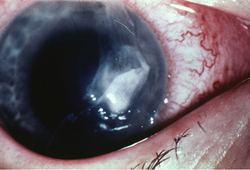

- Corneal hydrops

- Traumatic vision loss

- Optic neuritis

- Papilledema

- Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON)

- Acute angle-closure glaucoma

- Retinal detachment

- Postoperative endophthalmitis

- Central retinal artery occlusion

- Pituitary apoplexy

- Arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy/giant cell arteritis

- Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Cancer-associated retinopathy

Contributors

Authors

Jeffrey R. SooHoo, MD, MBA

Associate Professor

Sue Anschutz-Rodgers Eye Center

Department of Ophthalmology

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Aurora

CO

Disclosures

JRS declares that he has no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

Dr Jeffrey R. SooHoo would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr Prem S. Subramanian, the previous contributor to this topic.

Disclosures

PSS declares that he has no competing interests.

Peer reviewers

Andrew G. Lee, MD

The H. Stanley Neuro-ophthalmology Professor of Ophthalmology, Neurology, and Neurosurgery

The University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics

Iowa City

IA

Раскрытие информации

AGL declares that he has no competing interests.

Robert Avery, MD, PhD

Professor of Ophthalmology

University of New Mexico Medical School

Albuquerque

NM

Раскрытие информации

RA declares that he has no competing interests.

Augusto Azuara-Blanco, PhD, FRCS(Ed), FRCOphth

Clinical Senior Lecturer

Health Services Research Unit

University of Aberdeen

Honorary Consultant Ophthalmologist

NHS Grampian

Aberdeen

UK

Раскрытие информации

AA-B declares that he has no competing interests.

Stephen Vernon, DM, FRCS, FRCOphth, FCOptom (Hon), DO

Special Professor of Ophthalmology

University of Nottingham

Consultant Ophthalmic Surgeon

Nottingham University Hospitals

Nottingham

UK

Раскрытие информации

None declared.

Peer reviewer acknowledgements

BMJ Best Practice topics are updated on a rolling basis in line with developments in evidence and guidance. The peer reviewers listed here have reviewed the content at least once during the history of the topic.

Disclosures

Peer reviewer affiliations and disclosures pertain to the time of the review.

Список литературы

Основные статьи

Rossi T, Boccassini B, Iossa M, et al. Triaging and coding ophthalmic emergency: the Rome Eye Scoring System for Urgency and Emergency (RESCUE): a pilot study of 1,000 eye-dedicated emergency room patients. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007 May-Jun;17(3):413-7. Аннотация

Bird AC, Bressler NM, Bressler SB, et al. An international classification and grading system for age-related maculopathy and age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995 Mar-Apr;39(5):367-74. Аннотация

Donahue SP, Baker CN; American Academy of Pediatrics; American Association of Certified Orthoptists; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Procedures for the evaluation of the visual system by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016 Jan;137(1). (Reaffirmed Feb 2022).Полный текст Аннотация

Статьи, указанные как источники

A full list of sources referenced in this topic is available to users with access to all of BMJ Best Practice.

Лифлеты для пациента

Glaucoma

Herpes simplex eye infection

Больше Лифлеты для пациентаВойдите в учетную запись или оформите подписку, чтобы получить полноценный доступ к BMJ Best Practice

Использование этого контента попадает под действие нашего заявления об отказе от ответственности