Aphasia is an acquired impairment of language that affects comprehension and production of words, sentences, and/or discourse. It is typically characterized by errors in word retrieval or selection, including:

Semantic paraphasias (substituting a semantically related word for a target word, e.g., calling a horse a cow)

Phonemic paraphasias (substituting one or more sounds in the word, e.g., calling a horse a force or using a non-word such as porse)

Neologisms (a series of sounds that do not comprise a word and are not similar to the target word)

Circumlocutions (e.g., calling a horse an animal that you ride with a saddle).

Typically, both oral and written language are affected, but occasionally only one modality of input or output is impaired.

Definitions: aphasia, dysarthria, and apraxia

It is important to distinguish aphasia from dysarthria or apraxia.

Aphasia is a selective impairment of language or the cognitive processes that underlie language. Individuals with dementia often have language problems, but they also have at least equally severe deficits in episodic memory, visuospatial skills, and/or executive functions (e.g., organization, planning, decision making).

Dysarthria is an acquired disorder of speech production due to weakness, slowness, reduced range of movement, or impaired timing and coordination of the muscles of the jaw, lips, tongue, palate, vocal folds, and/or respiratory muscles (the speech articulators).

Apraxia of speech is an impairment in the motor planning and programming of the speech articulators that cannot be attributed to dysarthria.

These 3 disorders can coexist, but often occur separately. They can be distinguished by evaluation of language (tests of word and sentence comprehension, naming, repetition, spontaneous speech, reading, and writing), as well as tests of articulation (tests assessing the strength, coordination, rate, and range of movement of the muscles of speech articulation) and motor speech programming.

Vascular classification of aphasias

The most common classification of aphasia divides the disorder into clinical syndromes of frequently co-occurring deficits that reflect the vascular territory affected in stroke.[1]Damasio AR. Aphasia. N Engl J Med. 1992 Feb 20;326(8):531-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1732792?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Hillis AE. Aphasia: progress in the last quarter of a century. Neurology. 2007 Jul 10;69(2):200-13.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17620554?tool=bestpractice.com

For example, the Western aphasia battery and Boston diagnostic aphasia examination were designed to distinguish vascular syndromes.[3]Kertesz A. Western aphasia battery. New York, NY: Grune and Stratton; 1982.[4]Goodglass H, Kaplan E. The Boston diagnostic aphasia examination. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger; 1972. The relationship between the symptoms and the vascular territory that is affected is not always consistent, but is more reliable acutely than chronically.[5]Ochfeld E, Newhart M, Molitoris J, et al. Ischemia in Broca area is associated with Broca aphasia more reliably in acute than in chronic stroke. Stroke. 2010 Feb;41(2):325-30.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2828050

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20044520?tool=bestpractice.com

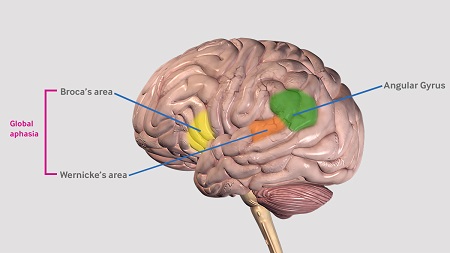

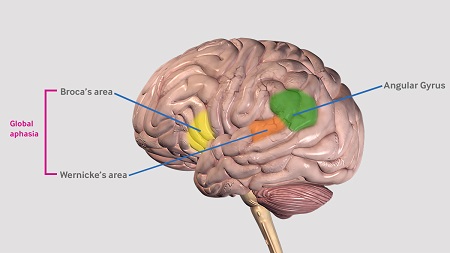

Broca aphasia is characterized by nonfluent, poorly articulated, and agrammatic speech output (in both spontaneous speech and repetition) with relatively spared word comprehension. Individuals with Broca aphasia often have difficulty understanding syntactically complex or semantically reversible sentences (e.g., "touch your nose after you touch your foot") but have little trouble understanding simple, semantically nonreversible sentences. This collection of syndromes is usually associated with ischemia or other lesions in the left posterior inferior frontal cortex, in the distribution of the superior division of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA).

Wernicke aphasia is characterized by fluent but meaningless speech output and repetition, with poor word and sentence comprehension. It is typically due to ischemia in the posterior superior temporal cortex, in the distribution of the inferior division of the left MCA.

Conduction aphasia is characterized by disproportionately impaired repetition with otherwise fluent speech. It is typically due to ischemia affecting the inferior parietal lobule.

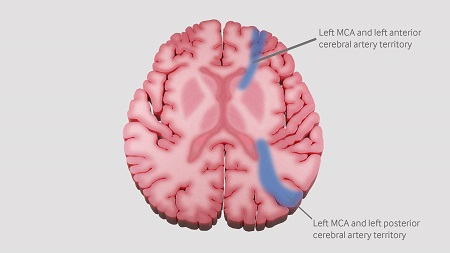

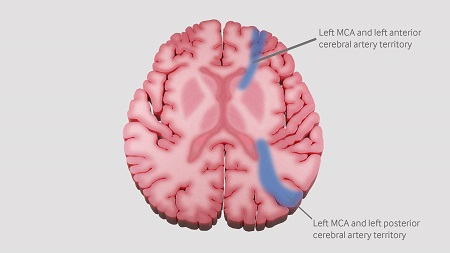

Transcortical aphasia is characterized by relatively spared repetition. Transcortical sensory aphasia usually results from ischemia involving the watershed area between the left MCA and left posterior cerebral artery (PCA) territory.

Transcortical motor aphasia usually results from ischemia involving the watershed area between the left MCA and left anterior cerebral artery (ACA) territory.

Mixed transcortical aphasia results from lesions in the left MCA and left PCA territory, in combination with the left MCA and left ACA territory. Repetition is the primary language ability.

Anomic aphasia is characterized by impaired naming and tissue damage in the angular gyrus or posterior middle/inferior temporal cortex.

Global aphasia denotes severe impairment in all aspects of language; the area of ischemia often involves both anterior and posterior language areas (Broca and Wernicke areas).[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Broca’s area, Wernicke’s area and the angular gyrus.Created by the BMJ Knowledge Centre. [Citation ends]. [Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Watershed areas between the anterior, middle and posterior cerebral artery territories.Created by the BMJ Knowledge Centre. [Citation ends].

[Figure caption and citation for the preceding image starts]: Watershed areas between the anterior, middle and posterior cerebral artery territories.Created by the BMJ Knowledge Centre. [Citation ends].

Fluency classification of aphasias

Fluency is a multidimensional term referring to the melody, prosody (pattern of stress and intonation), phrase length, rate of speech, grammaticality, effort, and articulatory precision of spontaneous speech. This is often tested by asking the patient to describe a complex picture depicting a number of activities.

Patients with fluent aphasia (melodious, effortless, well-articulated speech, which may have little content) tend to have posterior lesions in the left hemisphere, whereas patients with nonfluent aphasia (effortful, poorly-articulated speech, with more accurate content than speech sounds) tend to have anterior lesions in the brain. However, because fluency is a multidimensional term based on factors that can dissociate (grammatical accuracy, rate of speech, prosody, effort, articulatory precision, hesitations), it is often difficult to judge. A patient can be fluent on one dimension and nonfluent on another. Therefore, there is often disagreement between 2 people in judging fluency of an aphasic individual.

Fluent aphasias are typically due to lesions posterior to the central sulcus:

Wernicke aphasia with fluent, jargon speech and poor comprehension

Transcortical sensory aphasia, characterized by well-preserved repetition abilities in the context of poor comprehension and fluent but meaningless propositional speech

Conduction aphasia in which fluent spontaneous speech is preserved but repetition is impaired

Anomic aphasia with deficit of word finding and naming.

Nonfluent aphasias encompass the regions anterior to the central sulcus:

Broca aphasia

Transcortical motor aphasia with difficulty in initiating and organizing responses, but relatively preserved repetition

Mixed transcortical aphasia in which echolalia (repetition) is the only preserved language skill

Global aphasia characterized by severe impairment in speech and comprehension, and stereotypical utterances.

Disorders that only affect reading are referred to as types of alexia. Those that only affect writing are types of agraphia.[6]Black S, Behrmann M. Localization in alexia. In: Kertesz A, ed. Localization and neuroimaging in neuropsychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1994:152-84.[7]Hillis AE, Rapp BC. Cognitive and neural substrates of written language comprehension and production. In: Gazzaniga M, ed. The new cognitive neurosciences. 3rd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1994:755-88.

An important variable that complicates these deficit associations is the remarkable reorganization of structure-function relationships that often occurs after brain lesions, such that undamaged parts of the brain assume the functions of the damaged part over time, resulting in recovery from even the most severe aphasias (usually only after appropriate language therapy).

Ventral versus dorsal stream classification of aphasia

Ventral stream: a stream of processing that supports the interface between sensory-phonologic networks with semantic-conceptual network ("sound to meaning"), from Heschl gyrus bilaterally through the left temporal cortex, with widespread connections to semantic representations bilaterally. Lesions in the ventral stream disrupt word comprehension as well as sentence comprehension.[8]Hickok G, Poeppel D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007 May;8(5):393-402.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17431404?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Saur D, Kreher BW, Schnell S, et al. Ventral and dorsal pathways for language. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Nov 18;105(46):18035-40.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2584675

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19004769?tool=bestpractice.com

Dorsal stream: a stream of processing that supports the interface between sensory-phonologic networks and motor-articulatory networks ("sound to speech"), from Heschl gyrus bilaterally through left supramarginal gyrus and inferior frontal gyrus. Lesions in dorsal stream disrupt word and sentence repetition, grammatical sentence production, and speech articulation.[8]Hickok G, Poeppel D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007 May;8(5):393-402.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17431404?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Saur D, Kreher BW, Schnell S, et al. Ventral and dorsal pathways for language. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Nov 18;105(46):18035-40.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2584675

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19004769?tool=bestpractice.com

Follow-up treatment

After identifying and treating the underlying cause of aphasia, such as acute stroke or herpes encephalitis, patients may have a residual aphasia. Such aphasic individuals benefit from referral to a speech language pathologist specializing in aphasia therapy.

Treatment should be individualized to address the person's residual deficits, communicative needs and priorities, and available resources.[10]Hillis AE, Heidler J. Contributions and limitations of the "cognitive neuropsychological approach" to treatment: illustrations from studies of reading and spelling therapy. Aphasiology. 2005;19:985-93. Therapy often addresses the impaired cognitive processes underlying the individual's altered performance of language tasks. It is sometimes argued that intensive therapy (e.g., 5 days per week) is often more effective than less intensive therapy, unless the person is able to practice emerging skills on their own, often with the aid of a computer.[11]Bhogal SK, Teasell R, Speechley M. Intensity of aphasia therapy, impact on recovery. Stroke. 2003 Apr;34(4):987-93.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.STR.0000062343.64383.D0

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12649521?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Brady MC, Kelly H, Godwin J, et al. Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD000425.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27245310?tool=bestpractice.com

However, the dose (number of sessions) may actually be more important than the intensity.[13]Cherney LR, Patterson JP, Raymer A, et al. Evidence-based systematic review: effects of intensity of treatment and constraint-induced language therapy for individuals with stroke-induced aphasia. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008 Oct;51(5):1282-99.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18812489?tool=bestpractice.com

Speech and language therapy can significantly improve functional communication, comprehension, and production of speech.[12]Brady MC, Kelly H, Godwin J, et al. Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD000425.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000425.pub4/full

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27245310?tool=bestpractice.com

[  ]

In people with aphasia following stroke, how does the use of speech and language therapy affect outcomes?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.1384/fullПоказать ответ Alternatively, caregivers can be trained by the speech language pathologist to provide effective practice.[14]Aten JL, Caligiuri MP, Holland AL. The efficacy of functional communication therapy for chronic aphasic patients. J Speech Hear Disord. 1982 Feb;47(1):93-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7176583?tool=bestpractice.com

Therapy might be augmented with medications, such as memantine or donepezil, or with transcranial direct current stimulation.[15]Berube S, Hillis AE. Advances and innovations in aphasia treatment trials. Stroke. 2019 Oct;50(10):2977-84.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025290

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31510904?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]Saxena S, Hillis AE. An update on medications and noninvasive brain stimulation to augment language rehabilitation in post-stroke aphasia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017 Nov;17(11):1091-1107.

https://www.doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2017.1373020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28847186?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]Elsner B, Kugler J, Pohl M, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for improving aphasia in adults with aphasia after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 May 21;5:CD009760.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009760.pub4

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31111960?tool=bestpractice.com

Larger randomized controlled trials are needed to determine whether these interventions have a significant benefit over speech and language therapy alone.

]

In people with aphasia following stroke, how does the use of speech and language therapy affect outcomes?/cca.html?targetUrl=https://cochranelibrary.com/cca/doi/10.1002/cca.1384/fullПоказать ответ Alternatively, caregivers can be trained by the speech language pathologist to provide effective practice.[14]Aten JL, Caligiuri MP, Holland AL. The efficacy of functional communication therapy for chronic aphasic patients. J Speech Hear Disord. 1982 Feb;47(1):93-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7176583?tool=bestpractice.com

Therapy might be augmented with medications, such as memantine or donepezil, or with transcranial direct current stimulation.[15]Berube S, Hillis AE. Advances and innovations in aphasia treatment trials. Stroke. 2019 Oct;50(10):2977-84.

https://www.doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025290

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31510904?tool=bestpractice.com

[16]Saxena S, Hillis AE. An update on medications and noninvasive brain stimulation to augment language rehabilitation in post-stroke aphasia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017 Nov;17(11):1091-1107.

https://www.doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2017.1373020

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28847186?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]Elsner B, Kugler J, Pohl M, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for improving aphasia in adults with aphasia after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 May 21;5:CD009760.

https://www.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009760.pub4

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31111960?tool=bestpractice.com

Larger randomized controlled trials are needed to determine whether these interventions have a significant benefit over speech and language therapy alone.

Log in or subscribe to access all of BMJ Best Practice

]

]