Olfactory loss has been linked to a variety of causes and can profoundly influence a patient's quality of life.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that olfactory dysfunction affects approximately 22% of the general population; however, estimated prevalence rates vary significantly according to assessment techniques used, definitions of impairment, and the population sampled.[1]Whitcroft KL, Altundag A, Balungwe P, et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction: 2023. Rhinology. 2023 Oct 1;61(33):1-108.

https://www.rhinologyjournal.com/Abstract.php?id=3097

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37454287?tool=bestpractice.com

[2]Desiato VM, Levy DA, Byun YJ, et al. The prevalence of olfactory dysfunction in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2021 Mar;35(2):195-205.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1945892420946254

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32746612?tool=bestpractice.com

Prevalence of olfactory impairment increases with age and male sex; some degree of olfactory dysfunction may be present in more than 50% of adults ages over 65 years.[1]Whitcroft KL, Altundag A, Balungwe P, et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction: 2023. Rhinology. 2023 Oct 1;61(33):1-108.

https://www.rhinologyjournal.com/Abstract.php?id=3097

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37454287?tool=bestpractice.com

[3]Graves AB, Bowen JD, Rajaram L, et al. Impaired olfaction as a marker for cognitive decline: interaction with apolipoprotein E epsilon4 status. Neurology. 1999 Oct 22;53(7):1480-7.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10534255?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Pinto JM, Wroblewski KE, Kern DW, et al. The rate of age-related olfactory decline among the general population of older U.S. adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015 Nov;70(11):1435-41.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4715242

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26253908?tool=bestpractice.com

[5]Seubert J, Laukka EJ, Rizzuto D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of olfactory dysfunction in old age: a population-based Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017 Aug;72(8):1072-9.

https://academic.oup.com/biomedgerontology/article/72/8/1072/3746132

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28444135?tool=bestpractice.com

In one cross-sectional sample of American adults with mean age 68 years, approximately 22% were unable to identify four or more odors using a validated odor identification task.[6]Pinto JM, Schumm LP, Wroblewski KE, et al. Racial disparities in olfactory loss among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014 Mar;69(3):323-9.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3976135

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23689829?tool=bestpractice.com

Older African-Americans and Hispanic Americans were more likely to suffer from age-related olfactory dysfunction than white Americans.[6]Pinto JM, Schumm LP, Wroblewski KE, et al. Racial disparities in olfactory loss among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014 Mar;69(3):323-9.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3976135

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23689829?tool=bestpractice.com

Olfactory dysfunction prevalence estimates are generally higher when psychophysical (objective) tools, rather than subjective assessment techniques, are used to assess olfactory dysfunction.[1]Whitcroft KL, Altundag A, Balungwe P, et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction: 2023. Rhinology. 2023 Oct 1;61(33):1-108.

https://www.rhinologyjournal.com/Abstract.php?id=3097

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37454287?tool=bestpractice.com

[4]Pinto JM, Wroblewski KE, Kern DW, et al. The rate of age-related olfactory decline among the general population of older U.S. adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015 Nov;70(11):1435-41.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4715242

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26253908?tool=bestpractice.com

[5]Seubert J, Laukka EJ, Rizzuto D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of olfactory dysfunction in old age: a population-based Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017 Aug;72(8):1072-9.

https://academic.oup.com/biomedgerontology/article/72/8/1072/3746132

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28444135?tool=bestpractice.com

[7]Hannum ME, Ramirez VA, Lipson SJ, et al. Objective sensory testing methods reveal a higher prevalence of olfactory loss in COVID-19-positive patients compared to subjective methods: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chem Senses. 2020 Dec 5;45(9):865-74.

https://academic.oup.com/chemse/article/45/9/865/5912953

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33245136?tool=bestpractice.com

Severe olfactory dysfunction or complete olfactory loss (anosmia) is relatively uncommon in the general population. Prevalence estimates generally range from approximately 1% to 5% of the general population.[8]Pinto JM, Kern DW, Wroblewski KE, et al. Sensory function: insights from Wave 2 of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014 Nov;69 Suppl 2(suppl 2):S144-53.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4303092

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25360015?tool=bestpractice.com

[9]Landis BN, Konnerth CG, Hummel T. A study on the frequency of olfactory dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 2004 Oct;114(10):1764-9.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15454769?tool=bestpractice.com

COVID-19 pandemic

The global COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted prevalence rates of olfactory dysfunction, creating an additional cohort of people affected by both acute and postinfectious impairment or loss of olfactory function.[1]Whitcroft KL, Altundag A, Balungwe P, et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction: 2023. Rhinology. 2023 Oct 1;61(33):1-108.

https://www.rhinologyjournal.com/Abstract.php?id=3097

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37454287?tool=bestpractice.com

Systematic reviews and cohort studies have reported olfactory dysfunction prevalence of between 48% and 86% in COVID-19 patients.[10]Saniasiaya J, Islam MA, Abdullah B. Prevalence of olfactory dysfunction in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis of 27,492 patients. Laryngoscope. 2021 Apr;131(4):865-78.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7753439

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33219539?tool=bestpractice.com

[11]Rocke J, Hopkins C, Philpott C, et al. Is loss of sense of smell a diagnostic marker in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2020 Nov;45(6):914-22.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7436734

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32741085?tool=bestpractice.com

[12]Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 Aug;277(8):2251-61.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7134551

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32253535?tool=bestpractice.com

Prevalence of chemosensory dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 appears to differ between populations and ethnicities.[13]von Bartheld CS, Hagen MM, Butowt R. Prevalence of chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis reveals significant ethnic differences. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020 Oct 7;11(19):2944-61.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7571048

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32870641?tool=bestpractice.com

[14]von Bartheld CS, Wang L. Prevalence of olfactory dysfunction with the omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cells. 2023 Jan 28;12(3).

https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4409/12/3/430

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36766771?tool=bestpractice.com

[15]von Bartheld CS, Hagen MM, Butowt R. The D614G virus mutation enhances anosmia in COVID-19 patients: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies from South Asia. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2021 Oct 6;12(19):3535-49.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8482322

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34533304?tool=bestpractice.com

Etiology

In patients presenting primarily for loss of smell, the most commonly identified etiologies include a prior viral upper respiratory infection, head trauma, and underlying chronic sinus inflammation.[16]Deems DA, Doty RL, Settle RG, et al. Smell and taste disorders, a study of 750 patients from the University of Pennsylvania Smell and Taste Center. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:519-528.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2021470?tool=bestpractice.com

[17]Seiden AM, Duncan HJ. The diagnosis of a conductive olfactory loss. Laryngoscope. 2001 Jan;111(1):9-14.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11192906?tool=bestpractice.com

[18]Hoekman PK, Houlton JJ, Seiden AM. The utility of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnostic evaluation of idiopathic olfactory loss. Laryngoscope. 2014 Feb;124(2):365-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23775878?tool=bestpractice.com

These 3 causes account for over 50% of patients.

Pathophysiology

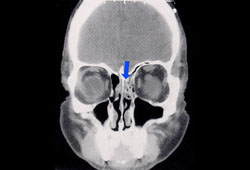

Olfactory loss may occur as a sensorineural loss, following degenerative changes in the olfactory neuronal receptors or neuroepithelium in the olfactory cleft.[19]Jafek BW, Hartman L, Eller PM, et al. Postviral olfactory dysfunction. Am J Rhinol. 1990 May;4(3):91-100. It may also occur as a conductive loss following an obstruction or inflammation within the nasal vault that prevents access of odorants to the olfactory receptors.

Types of olfactory loss

The loss may be complete (anosmia) or partial (hyposmia). It may be associated with perceived odor distortions (dysosmia) that are related to actual environmental odorant stimulation (parosmia) or occur spontaneously (phantosmia).

Presentation

Patients may present complaining of both smell and taste loss, or isolated taste loss, but on investigation their taste function is intact. This relates to the common confusion between taste and flavor. Taste sensation includes salt, sour, sweet, bitter, and umami (savory).[20]Lindemann B, Ogiwara Y, Ninomiya Y. The discovery of umami. Chem Senses. 2002 Nov;27(9):843-4. Flavor perception is based upon olfactory, tactile, and thermal sensations as well as taste, with olfactory being arguably the most important of these sensations. The loss of olfactory input makes food generally unappealing, something most patients notice very quickly. However, a true measurable taste loss is distinctly uncommon.[16]Deems DA, Doty RL, Settle RG, et al. Smell and taste disorders, a study of 750 patients from the University of Pennsylvania Smell and Taste Center. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:519-528.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2021470?tool=bestpractice.com

Treatment

For patients with olfactory loss due to an inflammatory process, reducing inflammation and obstruction in the nasal vault can effectively restore the ability to smell.[21]Kohli P, Naik AN, Farhood Z, et al. Olfactory outcomes after endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis: a meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016 Dec;155(6):936-48.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27576679?tool=bestpractice.com

Unfortunately, in most cases of olfactory loss, no specific therapy is available. However, patients will continue to seek medical opinion until they feel a thorough workup has been performed and a thorough explanation has been provided.[22]Harris R, Davidson TM, Murphy C, et al. Clinical evaluation and symptoms of chemosensory impairment: 1000 consecutive cases from the nasal dysfunction clinic in San Diego. Am J Rhinol. 2006 Jan-Feb;20(1):101-8.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16539304?tool=bestpractice.com

Some data suggest that olfactory training can increase the potential recovery after a postviral or post-traumatic olfactory loss.[23]Konstantinidis I, Tsakiropoulou E, Bekiaridou P, et al. Use of olfactory training in post-traumatic and postinfectious olfactory dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 2013 Dec;123(12):E85-90.[24]Pekala K, Chandra RK, Turner JH. Efficacy of olfactory training in patients with olfactory loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016 Mar;6(3):299-307.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4783272

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26624966?tool=bestpractice.com

Adverse sequelae

Safety issues related to olfactory loss include the inability to detect gas leaks, fire, or spoiled foods. However, the most significant impact for each patient is typically the loss in quality of life related to eating and drinking.[1]Whitcroft KL, Altundag A, Balungwe P, et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction: 2023. Rhinology. 2023 Oct 1;61(33):1-108.

https://www.rhinologyjournal.com/Abstract.php?id=3097

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37454287?tool=bestpractice.com

[25]Patel ZM, Holbrook EH, Turner JH, et al. International consensus statement on allergy and rhinology: olfaction. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022 Apr;12(4):327-680.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/alr.22929

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35373533?tool=bestpractice.com

This can be devastating. In some cases it may result in diminished appetite and inadequate nutritional intake, and in other cases it can cause increased oral intake and weight gain as patients seek chemosensory satisfaction. These consequences can have a negative impact on associated medical conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure. Invariably, patients receive little sympathy from friends and, on occasion, family and sometimes even from their physician.

For most patients who experience a loss of smell, no restorative therapy is available (unless the loss is secondary to inflammatory rhinosinusitis). Therefore, while most patients do benefit from counseling regarding safety issues and flavor enhancement methods, any information regarding prognosis becomes very important. Studies suggest prognosis relates more to the severity of the initial loss (as confirmed on objective olfactory testing), the age and sex of the patient, smoking, and the presence of dysosmia, than to the etiology of sensorineural loss.[26]Hummel T, Lötsch J. Prognostic factors of olfactory dysfunction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Apr;136(4):347-51.

http://archotol.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=496192

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20403850?tool=bestpractice.com

[27]London B, Nabet B, Fisher AR, et al. Predictors of prognosis in patients with olfactory disturbance. Ann Neurol. 2008 Feb;63(2):159-66.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18058814?tool=bestpractice.com

Log in or subscribe to access all of BMJ Best Practice